Astigmatism (eye)

| Astigmatism | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | H52.2 |

| ICD-9 | 367.2 |

Astigmatism is an optical defect in which vision is blurred due to the inability of the optics of the eye to focus a point object into a sharp focused image on the retina. This may be due to an irregular or toric curvature of the cornea or lens. There are two types of astigmatism: regular and irregular. Irregular astigmatism is often caused by a corneal scar or scattering in the crystalline lens and cannot be corrected by standard spectacle lenses, but can be corrected by contact lenses. Regular astigmatism arising from either the cornea or crystalline lens can be corrected by a toric lens. A toric surface resembles a section of the surface of an American football or a doughnut where there are two regular radii, one smaller than another. This optical shape gives rise to regular astigmatism in the eye.[1] The first spectacle lenses that corrected astigmatism were made in Philadelphia in 1841.

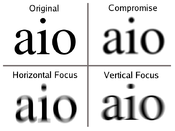

The refractive error of the astigmatic eye stems from a difference in degree of curvature refraction of the two different meridians (i.e., the eye has different focal points in different planes.) For example, the image may be clearly focused on the retina in the horizontal (sagittal) plane, but not in the vertical (tangential) plane. Astigmatism causes difficulties in seeing fine detail, and in some cases vertical lines (e.g., walls) may appear to the patient to be tilted. The astigmatic optics of the human eye can often be corrected by spectacles, hard contact lenses or contact lenses that have a compensating optic, cylindrical lens (i.e. a lens that has different radii of curvature in different planes), or refractive surgery.

Contents |

Types

Based on axis of the principal meridians

- Regular astigmatism – principal meridians are perpendicular

- With-the-rule astigmatism – the vertical meridian is steepest (an American football lying on its side).[2]

- Against-the-rule astigmatism – the horizontal meridian is steepest (an American football standing on its end).[2]

- Oblique astigmatism – the steepest curve lies in between 120 and 150 degrees and 30 and 60 degrees.[2]

- Irregular astigmatism – principal meridians are not perpendicular

Also known as Murdoch Syndrome (Ref: glastonbury Medics)

In With-the-rule astigmatism, the eye sees vertical lines more sharply than horizontal lines. Against-the-rule astigmatism reverses the situation. In With-the-rule astigmatism a minus cylinder is placed in the horizontal axis to correct the refractive error. Adding a minus cylinder in the horizontal axis makes the horizontal axis "steeper" which makes both axes equally "steep." In Against-the-rule astigmatism a plus cylinder is added in the horizontal axis.

Children tend to have With-the-rule astigmatism and adults tend to have Against-the-rule astigmatism.

Axis is always recorded as an angle in degrees, between 0 and 180 degrees in a counter-clockwise direction. 0 and 180 lie on a horizontal line at the level of the centre of the pupil, and as seen by an observer, 0 lies on the right of both eyes.

Based on focus of the principal meridians

- Simple astigmatism

- Simple hyperopic astigmatism – first focal line coincides with the retina while the second is located behind the retina

- Simple myopic astigmatism – first focal line is located in front of the retina while the second focal line is located on the retina

- Compound astigmatism

- Compound hyperopic astigmatism – both focal lines are located behind the retina

- Compound myopic astigmatism – both focal lines are located in front of the retina

- Mixed astigmatism – focal lines are on both sides of the retina (straddling the retina)

Prevalence

According to an American study published in Archives of Ophthalmology, nearly 3 in 10 children between the ages of 5 and 17 have astigmatism [3]. A recent Brazilian study found that 34% of the students in one city were astigmatic[4]. Regarding the prevalence in adults, a recent study in Bangladesh found that nearly 1 in 3 (32.4%) of those over the age of 30 had astigmatism[5].

A recent Polish study revealed that "with-the-rule astigmatism" may lead to the onset of myopia[6].

A number of studies have found that the prevalence of astigmatism increases with age[7].

Diagnosis

Symptoms

Although mild astigmatism may be asymptomatic, higher amounts of astigmatism may cause symptoms such as blurry vision, squinting, asthenopia, fatigue, or headaches.[8][9][10]

Signs and tests

There are a number of tests used by ophthalmologists and optometrists during eye examinations to determine the presence of astigmatism and to quantify the amount and axis of the astigmatism.[11] A Snellen chart or other eye charts may initially reveal reduced visual acuity. A keratometer may be used to measure the curvature of the steepest and flattest meridians in the cornea's front surface.[12] Corneal topography may also be used to obtain a more accurate representation of the cornea's shape.[13] An autorefractor or retinoscopy may provide an objective estimate of the eye's refractive error and the use of Jackson cross cylinders in a phoropter may be used to subjectively refine those measurements.[14][15] [16]. An alternative technique with the phoropter requires the use of a "clock dial" or "sunburst" chart to determine the astigmatic axis and power.[17][18] A keratometer may also be used to estimate astigmatism by finding the difference in power between the two primary meridians of the cornea. Javal's rule can then be used to compute the estimate of astigmatism.

Another refraction technique that is rarely used involves the use of a stenopaic slit (a thin slit aperture) where the refraction is determined in specific meridians - this technique is particularly useful in cases where the patient has a high degree of astigmatism or in refracting patients with irregular astigmatism.

Treatment

Astigmatism may be corrected with eyeglasses, contact lenses, or refractive surgery. Various considerations involving ocular health, refractive status, and lifestyle frequently determine whether one option may be better than another. In those with keratoconus, rigid gas permeable contact lenses often enable patients to achieve better visual acuities than eyeglasses. If the astigmatism is caused by a problem such as deformation of the eyeball due to a chalazion, treating the underlying cause will resolve the astigmatism. A person suffering from severe or irregular corneal astigmatism may be advised to wear rigid gas permeable contact lenses rather than the more comfortable soft contact lenses as this has the effect of masking the astigmatism.

See also

Related conditions

- Hyperopia

- Keratoconus

- Myopia

- Presbyopia

Other

- Eyeglass prescription

- Refractive surgery

- Lens (optics)

- Ophthalmology

- Optician

- Optometry

References

- ↑ Astigmatism - MayoClinic.com

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "Astigmatism at Buzzle.com". Buzzle.com. http://www.buzzle.com/articles/astigmatism.html. Retrieved 21 June 2008.

- ↑ Kleinstein RN, Jones LA, Hullett S, et al. (August 2003). "Refractive error and ethnicity in children". Arch. Ophthalmol. 121 (8): 1141–7. doi:10.1001/archopht.121.8.1141. PMID 12912692. http://archopht.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/abstract/121/8/1141.

- ↑ Garcia CA, Oréfice F, Nobre GF, Souza Dde B, Rocha ML, Vianna RN (2005). "[Prevalence of refractive errors in students in Northeastern Brazil."] (in Portuguese). Arq Bras Oftalmol 68 (3): 321–5. doi:/S0004-27492005000300009. PMID 16059562. http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0004-27492005000300009&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en.

- ↑ Bourne RR, Dineen BP, Ali SM, Noorul Huq DM, Johnson GJ (June 2004). "Prevalence of refractive error in Bangladeshi adults: results of the National Blindness and Low Vision Survey of Bangladesh". Ophthalmology 111 (6): 1150–60. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.09.046. PMID 15177965. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0161-6420(04)00131-9.

- ↑ Czepita D, Filipiak D (2005). "[The effect of the type of astigmatism on the incidence of myopia]" (in Polish). Klin Oczna 107 (1-3): 73–4. PMID 16052807.

- ↑ Asano K, Nomura H, Iwano M, et al. (2005). "Relationship between astigmatism and aging in middle-aged and elderly Japanese". Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 49 (2): 127–33. doi:10.1007/s10384-004-0152-110.1007/s10384-004-0152-1. PMID 15838729.

- ↑ Astigmatism

- ↑ Astigmatism symptoms and treatment on MedicineNet.com

- ↑ HIPUSA Astigmatism symptoms

- ↑ HIPUSA Astigmatism treatment

- ↑ Keratometry

- ↑ Corneal Topography and Imaging at eMedicine

- ↑ Graff T (June 1962). "[Control of the determination of astigmatism with the Jackson cross cylinder.]" (in German). Klin Monatsblatter Augenheilkd Augenarztl Fortbild 140: 702–8. PMID 13900989.

- ↑ Del Priore LV, Guyton DL (November 1986). "The Jackson cross cylinder. A reappraisal". Ophthalmology 93 (11): 1461–5. PMID 3808608.

- ↑ Brookman KE (May 1993). "The Jackson crossed cylinder: historical perspective". J Am Optom Assoc 64 (5): 329–31. PMID 8320415.

- ↑ Basic Refraction Procedures

- ↑ Introduction to Refraction

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||